Demonic Grounds & Eternal Recurrence of the History that Hurts: Study for Obedience (2023) by Sarah Bernstein

Part II of II. Warning: Contains Spoilers.

“Anatevka” from Fiddler on the Roof

In Part I, I attended to the interpersonal relationship and the feminist critique in Study for Obedience. In this part, I attend to the political allegory of Jewish scapegoating, the battle between dominant and subaltern geographic forces acting upon a contested land, oppositional magics – both white and black, the eternal recurrence of the Jewish “history that hurts” (to use a term from Saidiya Hartman) – of forced removal from Europe through exile or massacre, and the connections in the text between political violence and environmental devastation. For this analysis, I borrow the words of Bernice Rubens and utilize the theories outlined in Katherine McKittrick’s seminal work of critical geography, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (2006). Ultimately, Study for Obedience employs the Gothic aesthetic to express pessimism about the future – a future where the ongoing project, of “rational spatial colonization and domination”; of “the profitable erasure and objectification of subaltern subjectivities, stories, and lands” (McKittrick, “Introduction,” x); and of the refinement of space in favor of monocultures, ethnic homogenization, and rapacious industrial production and extraction, engenders monsters: unabating violence and desolation.

Bernice Rubens’ Proposal for an “Elected Member” Novel of Political Allegory.

Bernice Rubens on winning the Booker Prize – and the pleasure of writing

In this video, Bernice Rubens states,

The germ of Elected Member came from one of R.D. Laing’s phrases, not a phrase but an idea that he had, which was the basis of his therapy, that in every family there is one member who is elected to bear the neuroses of the others – the scapegoat, in the real sense – the goat that is the scape, as it were, and I had the idea that I could equate this theory of election with the fact that the Jews were the elected, chosen people of God. I don’t think the book works on that level, frankly, but that was the intention.

What a serendipitous coincidence to have watched that video just prior to reading Study for Obedience, because I think that Sarah Bernstein deliberately takes up this challenge to write a novel that foregrounds a Jewish woman who has been elected scapegoat by her family, her community of origin, and the Eastern European gentile community living in the valley near her brother’s estate.[i]

The idea of the scapegoat has two meanings. In the Hebrew Bible and ancient Jewish ritual, on Yom Kippur the Israelites would bring two goats as sin offerings before the high priests; by lots, one would be chosen for ritual slaughter to expiate the sin of the community, while the other would be cast out for Azazel into the desert – a remote, desolate part of the wilderness. Before the release of the scapegoat to Azazel, the entire people would symbolically transfer its sins onto the goat, rendering them pure: “Though your sins are scarlet, they shall be as white as snow” (Isaiah 1:18). In the sociological context, scapegoating is “the practice of singling out a person or group for unmerited blame and consequent negative treatment” (Wikipedia).

Study for Obedience employs both uses to make the protagonist into a scapegoat; she is both the figure of ritual sin transference and the one who is irrationally accused of improbable wrongdoing. Fulfilling the first meaning, the protagonist reflects that others are constantly transferring their sins onto her: throughout her life, they reveal their sins to her and then come to hate her for knowing their darkest secrets (15). Regarding the second meaning – becoming an object of scorn and blame for others’ misfortunes, the protagonist reveals,

Accepting that my arrival had coincided with the madness and necessary extermination of the cows, the demise of the ewe and her nearly born [stillborn] lamb, the dog’s phantom pregnancy, the containment of domestic fowl, a potato blight […] – acknowledging that all these events had occurred in quick succession more or less upon my arrival in the place, and admitting that not one of these things had happened singly in recent memory, that the town and surrounding areas had actually lived through a blessed and prosperous fifty years, and that these unfortunate events had still less ever, in recorded history, happened simultaneously – granting all this, yes, it was still difficult for me to accept the bad feeling of the townspeople (129-130).

Earlier, she writes simply, “I knew they were right to hold me responsible” (2). The protagonist also aligns her desires to her fate as the scapegoat marked for Azazel and cast into the desert: “I thought of the desert, which seemed to me an ideal habitat, a habitat so full of nothing, replete with it [...]. Someday, […] I would withdraw to the desert, […] to some place in the American Southwest, withdraw to a cave in the hills, a wooden house in a valley, live in silence in among my surroundings” (86). Her family calls her inconsiderate for preferring austerity and desolation (92-93).

The townspeople – “grave and pious” (175), close to nature (51, 132) – are terrified of the female Jewish protagonist. They turn their babies away from her as from the petrifying image of Medusa (79) and panic at her approach (124). On the community farm on which she has volunteered, they relegate her to tasks that enable complete isolation (133, 167). On several occasions, she finds “the skinned remains of eviscerated rabbits in the garden” (115). One day at her brother’s house, “well after midsummer,” she writes,

I was leaning on the wall on the left side of the door when, looking over, I noticed a strange character carved into the upper third of the right-hand post […]. I had never before seen this carving, it was not from an alphabet familiar to me, certainly not Latin or Greek; not Cyrillic, Hebrew or Arabic, none of these, no. The appearance of the strange character – a rune? – did not especially faze me (155).

I interpret this symbol as a pre-Christian sign setting her apart and summoning her to an occult ritual, for later, the protagonist finds herself outside one night, seeing the first stars twinkling in the sky. Two figures clad in white approach her, the protagonist expresses her willingness to die (175, I’ll return to this later), and then she leads them to the church, whose windows are “aflame with candles, more candles than [she] had ever seen in one place” (175-176). She enters the church for the first and last time (176): “[t]here in all the pews sat the townspeople, all wearing the same white sweatsuit. They looked comfortable. Their faces flickered in the candlelight” (176). Matching white sweatsuits! White is our clue that they’re engaging in a purification ritual to expiate their sin. Oh my God, I wonder as I read, are they going to murder her in an occult ritual to remove the curse on their land? Is this the inevitable corollary of her scapegoating? Are they going to burn the witch?

“Burn the Witch” by Radiohead

Like a bride in a demented wedding ceremony, the protagonist walks up the aisle of the church to the dais. On the dais, she circles the table displaying the evidence of her guilt, including the six piglets crushed by their mother sow, three times (177): “I walked slowly down the church’s central aisle, […] I approached the long table, reaching it at last, looking from the hessian sack to each of the reed men, the talismans, my eyes skipping over the tiny pink things on the first go, on second go – finally on my third pass I forced myself to discern the character of the tiny and pink things in the candlelight” (177).

Why does she thrice circle the table? The only reason I can think of is the kapparot scapegoating ritual:

Kapparot is a custom in which the sins of a person are symbolically transferred to a fowl. The custom is practiced in certain Orthodox circles on the day before Yom Kippur (in some congregations […]. […][A] rooster (for a male) or a hen (for a female) is held above the person’s head and swung in a circle three times, while the following is spoken: ‘This is my exchange, my substitute, my atonement; this rooster (or hen) shall go to its death, but I shall go to a good, long life, and to peace.’ The hope is that the fowl, which is then donated to the poor for food, will take on any misfortune that might otherwise occur to the one who has taken part in the ritual in punishment for his or her sins (Jewish Virtual Library).

After circling the table three times, the protagonist bows her head before the piglets, moves behind the dais, and looks out on the assembly for a while (184). Then she steps down (188) and leaves the church.

Contrary to her expression of thanatos (death drive) – her “unkillable longing for self-annihilation” (175), the protagonist does not die. While initially I thought that walking off the stage symbolized the protagonist’s affirmation of her right to the land (more on this idea in the demonic grounds section), now I interpret the ritual as forfeit: divorcing herself from the land and its inhabitants. Through her symbolic ritual of exile into the desolate space of social abandonment reserved for Azazel, she cuts herself off from the land and relinquishes her right to possess it. At the end of the novel, the protagonist and her brother seem confined to his house and property (189). Reverting to her earlier habit of “looking out the window […], [with her] chin resting on the sill so that [she] could get a sense of the weather, of the [place], without being in among either” (92), she gazes out the window of her brother’s house and muses that the townspeople “will not come because they do not need to” (189); her exile is self-imposed, she will stay within the boundaries of the property, and she will be perfectly obedient. “Nevertheless,” she says to herself, softly, “I am living, I claim my right to live” (189). Since, as I argued in the first essay, the protagonist’s motives are to “care” for her brother by holding him hostage indefinitely in the realization of her obsessive possession and Munchausen by proxy syndrome, she abandons interest in the project of being reintegrated into the land.

And now, a loosely-related musical interlude.

“All I Really Want” by Alanis Morissette

Demonic Grounds.

Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (2006) by Katherine McKittrick illuminates geography as a terrain of social struggle, beset by historical processes that naturalize some people to a specific place and render others alien outsiders to it. Her objectives are “to make visible social lives which are often displaced, rendered ungeographic” (McKittrick, x), to call attention to the “social production of space” (McKittrick, xi), and to signal that space, which includes its human and nonhuman inhabitants, is not permanently fixed and unwavering but is alterable and dynamic, open to change and flux. Dominant geography (or traditional geography) refers to the geographic ideology, or knowledge-power, of the hegemonic group, which has normalized its exclusive claims on the land by subjugating its exogenous “others” – largely through expulsion, expropriation, and extermination. In contradistinction to this term, McKittrick poses oppositional geography or Black women’s geography – and to borrow from her concept to discuss the erasure and violent removal of Jews from lands they inhabited for hundreds of years, I will employ the terms oppositional geography, subaltern geography, and transformative geography. Transformative geography seeks to challenge, subvert, resist, and alter dominant geography’s ways of seeing and knowing through respatializations: “if practices of subjugation are also spatial acts, then the ways in which” subjugated women “think, write, and negotiate their surroundings are intermingled with place-based critiques, or respatializations” (McKittrick, xix). By engaging with the epistemologies, languages, subjectivities, and concrete spaces of oppositional subaltern geographies, “openings are made possible for envisioning an interpretive alterable world, rather than a transparent and knowable world” (McKittrick, xiii). One way that subaltern (subjugated or colonized) subjects imagine and enact respatialization in order to effect transformative geography is by conjuring the land as a demonic ground. The demonic ground has three characteristics:

1. It has an actively supernatural element.

2. It provides a nondeterministic schema that cannot predict future outcomes.

3. It highlights the absented presence of people who were violently removed from the land (i.e., it summons the ghosts haunting the place). [ii]

For McKittrick, Sylvia Wynter’s theorization of demonic grounds creates new possibilities for imagining humane and “just conceptualizations of space and place” (McKittrick, xxvi); it creates a new epistemology and a new direction or telos (McKittrick, xxvi). In addition to demonic grounds, McKittrick asserts that Édouard Glissant’s poetics of landscape, an aesthetic that spiritually and intimately binds people to the land, is another important expressive act that enables respatialization in favor of transformative geography (McKittrick, xxi-xxii). Study for Obedience highlights geography as a terrain of struggle between violent domination and transformative liberation by conjuring the location of the novel’s events as a demonic ground and by engaging in a poetics of landscape. Which side wins?

In the novel, the landscape is constantly shifting in the battle between dominant geography’s ironclad supremacy and cracks in its armor, through which glimmers of resistance and transformation can escape. The location constitutes a contested, demonic ground via all three criteria – the supernatural, nondeterminism, and a landscape haunted by the absented presence of historical ghosts – and the protagonist expresses a poetics of landscape.

A War of Magics.

Regarding the supernatural, Study for Obedience can also be figured as a war between white and black magics that act on both the protagonist and on the townspeople and whose values change according to perspective. Whereas the witch-hunting hysteria that swept Europe is intertwined with the history of anti-Jewish hatred, scapegoating, and violent persecution, the text is drawing on the centuries-old trope of accusing the Jewess of witchcraft.

For instance, when she starts weaving baskets and making grass dolls, a supernatural presence possesses the protagonist: “What could I possibly have wanted with those switches of willow? It was as if I was animated by some external force that directed my actions, […] some current in my body guiding my hands” (54). Later, when she makes the talismans and distributes them to the townspeople, she remarks, “I cannot now explain what impelled me to go into the forest that night, to pick the herbs and grasses I knew so well by sight though not by name, to weave them into shapes of some significance to me, an then to proceed on my bicycle, […] to deliver these several talismans to select locations in the village” (71). Possessed by a spirit, she delivers the dolls, ostensibly to facilitate restitution and goodwill between her people and the people of the town. She intends these dolls as offerings of gratitude and good fortune, reciting “quiet words of devotion” before depositing them (71).

The protagonist believes that she is transmitting good magic in order to reconcile herself to the land and its people – to change the course of her people’s history on the land. The townspeople, on the contrary, interpret her presence and her dolls as evil sorcery, a curse that has brought plague and ruin to their lives and their land (129-130). They respond in kind with the dark arts, leaving eviscerated rabbits in her garden (115). Then they dig a mass grave for her grass dolls, recite prayers, and ritualistically bury them (126-127), symbolically reenacting the mass murder operations (“Aktionen” in the “Holocaust by bullets”) and burial into mass graves of approximately 1.5 million Jews that occurred in numerous Eastern territories during the Holocaust, such as the mass grave site at Babi Yar. In response to the townspeople’s black magic, the protagonist performs “various rituals to ward off the evil eye” (128) and protect herself from harm. Both sides attribute a dark occult force to the other and remain irreconcilable to each other, and the protagonist’s attempts at transforming geography to accommodate her presence – intervening in the eternal recurrence of a history and fated future that hurt – are ultimately met with a brutally revanchist dominant geography that maintains her alienation.

Disparate magics are working upon the protagonist as well. Captivated by the beauty of her surroundings, the protagonist expresses a sense of belonging and rootedness to the place, as if held there by a mysterious force (46-47), and confesses that her “desire increased to stay in the place forever” (33). She feels spiritually, psychically, and somatically connected to the spirit of the land: “I experienced a physical pain as I watched the crooked pines blow in the wind” (32).

At the same time, her imagination conjures various scenarios in which the land conspires against her to cause “any number of violent incidents resulting in […] an array of potential painful deaths” (33), prompting her to ask, “what was to be done when everything was refused in advance?” (34).

“Who By Fire” by Leonard Cohen (adapted from Jewish liturgy recited during the Days of Awe)

Later the protagonist feels that the land is “working to expel” her (74). Although the protagonist has a talent for learning foreign languages, she is hopelessly unable to learn the language of the place she inhabits (49-50) and is plagued by “aphasia,” “dysphasia,” and “aphonia” (63), preventing her from making herself intelligible to the townspeople. Since she has proven able to acquire new languages, there is a dark magic playing on her, ensuring her linguistic alienation from the land and its inhabitants: “Since I could not interpret the diacritic marks of the language of the country, the shape of the words in my mouth could only be an approximate homophonic translation. And so although I walked in the forest nearly every day of the year, I felt perpetually estranged from it” (46).

The protagonist’s linguistic alienation signals not only dark magic but the absented presence of her people’s history. It is one absented presence, or ghost, of many in the text. The perpetual return of spectral and absented presences tells us that we are on a demonic ground engaged in a cosmic battle between the enclosure of removal and the disclosure, or opening up, of a space of new possibilities. Her ancestors undoubtedly spoke Yiddish, the lingua franca of Ashkenazi Jews for nearly a thousand years, not Russian or Ukrainian, and their linguistic separateness, like their religious separateness, facilitated their unassimilability into the dominant culture. For the protagonist, her linguistic separation perpetuates her solitary confinement and purgatory.

The land carries the memory of its ghosts. For instance, the protagonist witnesses the “strange behaviour of the dogs”: “Three times a day, at daybreak, at noon, at sunset, in all corners of the township however far-flung, every canine, as if mobilized by some mysterious force, stood to attention and howled in one long, unbroken, collective howl” (56). The dogs’ howling is timed to echo the three Jewish daily prayers – shacharit (dawn prayer), mincha (afternoon prayer), and ma’ariv (evening prayer), conjuring the ghosts of millions of Jewish men, women, and children whose lives held by the rhythms of those devotional rites, people who were butchered in pogroms and annihilation campaigns on the land she treads.

After her brother leaves, the protagonist goes for daily walks in the woods and pays careful attention to her natural surroundings (45). Her perception shifts, relating, “It was disorienting to walk in the woods day after day, to mark the astonishing and impossible changes from one day to the next. I was dizzy with it all. I felt as though I were remembering something I had long forgotten” (45). Daily she visits a lake where she lies on her front at the water’s edge:

[T]he silence rang and rang. As I returned to this lake over the months that followed, I learned that this quality was intrinsic to the place: it was not merely the contrast of the wind and the stillness; the thrum of silence at the lake exerted a physical pressure that, while not painful exactly, overwhelmed me, pinning me to the spot, often for hours at a time. At times the silence was a sound […], it was tangible, I felt it as much as I heard it, and yet I knew that what I felt and heard was a nothing, something that was not there. There were no trees for the wind to blow through, […] only the ground itself […]. And yet there it was: presence and absence twisting together (47, emphasis added).

The thrumming she hears is the blood of her people crying out from below ground. In Genesis, God says to Cain, your “Listen: your brother’s bloods are crying out from the ground” (Gen 4:10). In the original Hebrew, bloods are pluralized. Cain represents the one who murders his brothers and sisters in the human family.

“Seeking an Answer” by Hayehudim (click for English lyrics)

Eternal Recurrence of the “History that Hurts.”

“How ineluctable the paths one treaded!” Study for Obedience (111)

Regardless of the protagonist’s exertions to create a life for herself in this place, which requires a “disclosure of space” (31), the land and its inhabitants ultimately reject her, signaling a triumph of dominant geography:

I was not from the place, and so I was not anything. I was a nothing, a stranger who was not wanted but who nevertheless imposed herself continually, day after day, a kind of spectral presence hovering at the edges of the life of the town, whose intentions were obscure and who for some reason evinced a terrible fidelity to the idea of staying put (75).

Despite her efforts to “reorient” herself to foster a “disclosure of space” (31) – thus to change the fate of her people, she ultimately expresses hopeless surrender, that her people’s perennial alienation is a fait accompli, for everything has been refused in advanced (34). After the townspeople’s occult ostracism and ritualized social abandonment of her, the protagonist then resolves to forget “the grasses […], […] the night woods, the several woven amulets placed so tenderly on doorsteps and in haylofts, in naves and on cobbles, lying buried now underneath the silt by the river” (136). Active and deliberate rather than organic and involuntary, this forgetting is an apology for reaching “out, something I never ought to have done” (136). She had “reached out over that unthinkable abyss of history” (136) and was met only with disappointment and refusal. The protagonist thus obliterates the memory of her solicitous and conciliatory gestures: “I turned back to my project of self-improvement, the searching for the unit of illumination, the never finding it, never stirring from the field of the possible, such were the operations of the doomed inquiry into the soul, the pursuit of a state of gravity and grace” (136-137).[iii]

Finally, she concludes,

One’s orientation to the world was a fixed point from which one made one’s observations, this at any rate was what the townspeople felt, had always felt, about my brother, even before my arrival: one man could be managed, but any more, any different, and the landscape began to change. One dipped in the valley. It was not that one was contemptible, not necessarily, but rather that one’s presence wrung out a deeper sense of abjection, so much more primal than the disgust I usually aroused. Here, one was forced back into one’s context, given a kind of depth, no longer an atomised individual but part of a structure of feeling that was centuries old. How capacious it was in comparison! How inevitable! How beautiful to be conscious of the inexorable process of eternal recurrence. I felt held. I hoped my brother would someday feel held by it, too (183-184, emphasis added).

Eternal recurrence is associated with the ancient Greek belief that the world repeats the same immutable course of historical events ad infinitum, going through infinite cycles of birth, death, and rebirth. While the Judeo-Christian tradition emphasizes free will and a turn away from an unalterable fate or destiny, Friedrich Nietzsche resurrects the fatalistic Greek concept in his philosophy. One of my favorite novels, The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera, dramatizes the tension between the ideas of eternal return in accordance with cosmic predestination and the singular occurrence born of an independent free will. Study for Obedience also dramatizes this tension, ultimately siding with the forces of eternal recurrence that dwarf the individual struggling to break free.

That Unthinkable Abyss of History.

“And so as I wielded the axe in my brother’s name, and as I watched the bare branches toss against the sky, a feeling came over me, or else I felt surrounded by a way of feeling that preceded me an would carry on once I was gone, an awareness of catastrophe just beyond the garden gate, some small and precipitate decision of my own sending me careering towards it. After all, there was nowhere else to go, everything reached its terminus. It was an anticipation congenital, intermittent and providential. It was barely concealed and not totally unwanted. All this was perhaps a problem of inheritance, I thought, the lullabies of my people, […] singing of burning villages, of exile.” Study for Obedience, pp. 39-40

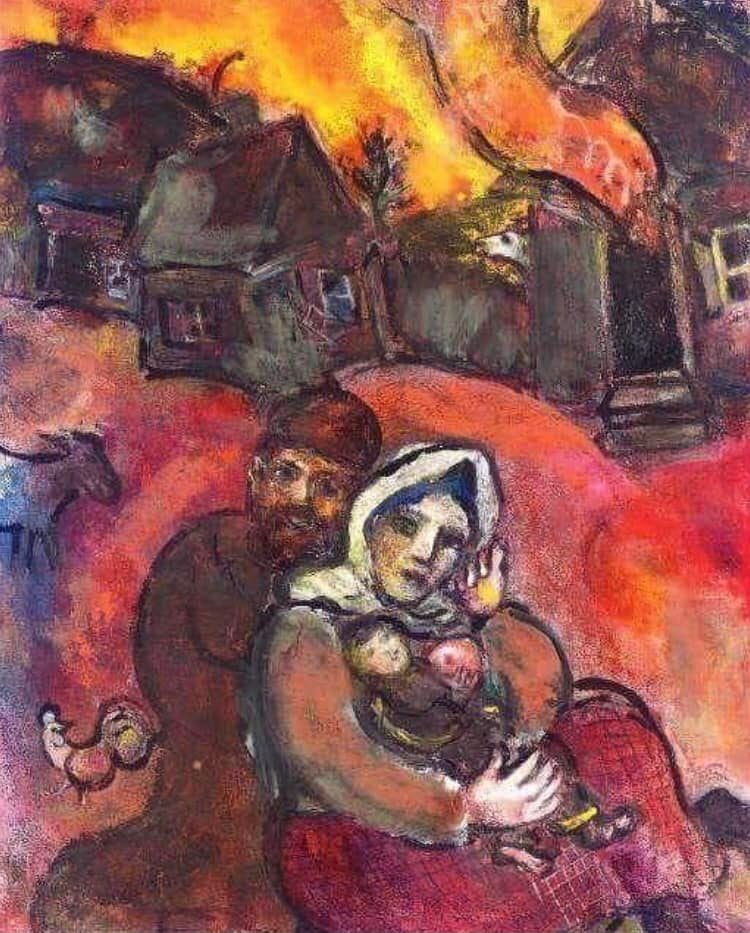

“Ukrainian Family” (1942) by Marc Chagall

The text summons the history of the protagonist’s people, naming the violence “unthinkable” (136). The reader is challenged to consider how a place that had millions of Jewish inhabitants – for centuries – is now entirely devoid of them. Content warning: for readers who want to avoid reading about the traumatic history evoked and Gothicized in the text, please feel free to skip to the next section. For now, it’s time to confront and remember the history, to bring it to the fore.

In The Lost: A Search for Six of the Six Million (2006), professor of classics Daniel Mendelsohn documents his attempts to recover what happened to his relatives in their small Ukrainian village during the Holocaust. What happened to his relatives is representative of what happened to Jews all along the Eastern territories in the former areas of Galicia – his ancestors were Galitzianers, as were mine – and the Pale of the Settlement, where most Jews living in the Russian Empire were ghettoized. Mendelsohn conducts interviews and pores over archival documents to uncover the occluded history of what actually happened to his family in a little town called Bolechów in what is now western Ukraine. The decimation of the Jewish population in Bolechów occurred over two Aktionen, or campaigns of slaughter, during the Nazi occupation.

An account of the first Aktion in Bolechów:

On Tuesday 28 October 1941 at 10 am, two cars arrived from Stanisławów, they drove up to the town hall. In one car were Gestapo men in black shirts. In the other were [Ukrainian Auxiliary Policemen] in yellow shirts and berets with shovels on them. The latter immediately drove to Taniawa to dig one large grave. […] A Ukrainian was assigned to each Gestapo man and these pairs went with a list [of the town’s wealthiest and most intelligent Jews] set by city hall for the town. […] At 12 o’clock, they started taking people from their houses and the streets. Near houses where a Gestapo man left, a crowd of Ukrainians arrived, who poured into the house to rob it after the Jews were led to the town square. […] They sent the Jews to the Dom Katolicki [Catholic community center] on Wołoski Field. […] Nine hundred people were packed into the hall. People were stacked on one another. Many suffocated. They were killed in the hall, shot or simply hit over the head with clubs and sticks, right there in the hall. […] People were beaten without any reason. […] The people were kept this way from 28 to 29 October without food or water until 16.00. At 16.00, they were all taken by [train] cars to the woods in Taniawa, 8 – 10 km from Bolechów. About 800 people were shot there. There was a board over a ditch onto which people were forced and they were shot and fell into the grave (Mendelsohn, 208-209).

In the first Aktion in Bolechów, the Germans and their Ukrainian helpers took Jews on a list of the town’s “wealthiest and most intelligent” and “took them to forest and ravines or cemeteries, remote places where pits had been obligingly dug by, often, the locals, and they shot them there” (Mendelsohn, 221).

This is the historical backstory to Study for Obedience, as well as campaigns like the second Aktion in Bolechów, which was “a tiny part of Operation Reinhard – one aim of which, the records show, was to make the Generalgouvernement completely Judenrein, Jew-free” (Mendelsohn, 229).

An account of the second Aktion in Bolechów:

Men, women, and children were caught in their houses, attics, hiding places. About 660 children were taken. People were killed in the town square in Bolechów and in the streets. […] The [German Gestapo] and [Ukrainian Auxiliary Police] preyed especially on the children. They took the children by their legs and bashed their heads on the edge of the sidewalks, whilst they laughed and tried to kill them with one blow. Others threw children from the height of the first floor, so a child fell on the brick pavement until it was just pulp. The Gestapo men bragged that they killed 600 children and the Ukrainian Matowiecki (From Rozdoly near Zydaczowy) proudly guessed that he had killed 96 Jews himself, mostly children.

[…] In the action – September 1942 – which lasted three days, 600-700 children were killed and 800-900 adults. The rest of the Jews who had been captured [who were not shot or beaten to death], approximately 2,000, were taken to Belzec [extermination camp]. […] During the march to the train station in Bolechów for the transport to Belzec, they had to sing, particularly the song “My Little Town of Belz.” Whoever didn’t take part in the singing was beaten bloody on the shoulders and head with rifle butts (Mendelsohn, 227-229).

On their death march, the people are forced to sing a song of nostalgic longing for a once-beloved Jewish village (“shtetl”) on which an extermination camp has been erected.

“Mein Shtetele Belz”

Political Violence and Environmental Devastation.

“Don’t Drink the Water” by Dave Matthews Band

The opposing visions for the land have an environmental dimension as well. Dominant geography, carrying the baggage of Western colonial epistemologies, particularly mechanical philosophy (mechanism), reduces the world and everything in it to a series of machines, adjudging the earth and its dwelling places dead matter for human exploitation and plunder. It leaves ruin in its wake and causes the desertification of the world. Subaltern geography, on the other hand, organizes space according to traditional earth-revering epistemologies that honor the coexistence of all lifeforms, promote biodiverse habitats and thriving multispecies ecosystems, and live by the watchword take only what you need. It maintains refugia of symbiotic multispecies thriving. This duality reminds us that spaces are inherently and primordially multicultural (in the human and nonhuman senses); when we witness a space that is not – a monospecies forest, a monoculture agricultural farm, an industrial animal CAFO, a barren wind farm that blights the landscape, an ethnically homogeneous town – that space has been socially constructed as monolithic, ordered and simplified according to a specific logic of extraction and consumption.[iv] It’s neither natural nor as nature intended.

A strong current of environmental critique runs throughout Study for Obedience. The protagonist transcribes audio notes for a legal firm’s client, a “multinational oil and gas corporation” that is enacting retribution against a whistleblower who accuses it of poisoning waterways, the “destruction of ancient woodland, the decimation of at least two protected species of birds, the kidnapping of activists, and the corruption of public officials” (35). She contemplates her complicity, by working for this company, as a moral failure (37-38). Later, when the protagonist ventures into town, she notices that the “single fuel pump […] was owned and supplied by the company the legal firm I worked for was currently representing. Lives layered upon lives, the concentric logic of the world and its continual co-optations. I felt a motiveless sorrow” (68). Everything is connected, and the machinations of the evil corporation are inescapable.

The protagonist then recounts letters that her brother has been collecting from a local artisan, letters of political objection inveighing against the Home Office, protesting any and all interventions in the landscape for putatively ecological conservation and restoration purposes.[v] On the one hand, the state’s previous interventions in the landscape and history of social engineering have proven disastrous; on the other, the artisan ignores the social production/construction of space that has made possible the world in which he now lives, attributing his surroundings instead to the untouched workings of pristine Nature. He willfully ignores the fact that the world, in its current state, is constructed to run on fossil fuels, which even form the basis for conventional fertilizer (the world is eating fossil fuels!), and is organized into sanitized monocultural spaces of blight. None of this is natural and desirable; it is in fact ruinous and catastrophic! This blindness leads the protagonist to muse, “Soon we would no longer need to withdraw to the desert for a space of contemplation and self-abnegation. Soon, personal ascesis would arrive in the form of one more letter [from the artisan], one more mass mortality event, one more migration stopped by total annihilation” (70).

“Bad Dreams” by Joni Mitchell

The protagonist suggests that the artisan’s logic spells humanity’s doom, for it naturalizes the dominant geographic epistemology that has evacuated foreigners from social spaces and extinguished diverse habitats in favor of zones of imposed exclusion and desolation: one-species zoological enclosures, industrial CAFOs, ruined and depleted single-use landscapes, and captive spaces. The same logic that perpetuates ecological destruction also naturalizes a tribal competition for space that invariably exterminates the minority or less powerful Other. In Marxist terminology, the global colonial/capitalist system’s survival depends on endlessly recurring acts of primitive accumulation – violent expropriation, rape and pillage, violence and dispossession.

Further linking political violence to ecological destruction, the protagonist recalls her brother’s condescending harangue in which he sympathizes with the townspeople and their forebears, for what they called “efficiency,” “the rest of the world […] determined to be acts of barbarism” (145). The Nazis prided themselves on their efficiency in deploying Zyklon B to exterminate Jews, Roma, homosexuals, political dissidents, and the handicapped. They sanitized the land under Operation Reinhard, making it Judenrein, Jew-free. In a parallel vein, the extractive consumer system values efficiency; land management programs prioritize efficiency. Clear-cutting forests for monoculture farms. Destroying diverse ecosystems for industrial feed lots. Exploding mountain tops for coal removal. Stripping the land. Paving paradise and putting up parking lots. Fostering silent springs through weapons of chemical warfare rebranded as agricultural aids to guarantee more predictable yields. How a dominant group disposes of its exogenous others operates according to the logic of efficiency, same as industrialized farm and forest techniques under collectivization, the Green Revolution, and any number of other statecraft schemes. They all put the world in peril.

Finally, the protagonist contemplates the fact that we are all complicit in this great derangement, that we ensure its continuation: “Every single one of us on this ruined earth exhibited a perfect obedience to our local forces of gravity, daily choosing the path of least resistance, which while entirely and understandably human was at the same time the most barbaric, the most abominable course of action. So listen. I am not blameless. I played my part” (157).

And that is the scariest Gothic element of all.

“Big Yellow Taxi” by Joni Mitchell

[i] Study for Obedience explicitly refers to an elected member at two points: “[T]he elected member was often present at the disclosures, held as a sort of hostage in the complex social interaction where everyone feigned good cheer” (107), and “There was something unthinkable in other people, always, I felt that so keenly now […] as I saw more clearly that my position vis-à-vis the townspeople was an immovable one, that I had been elected for purposes whose meaning I still groped for, and for life” (150).

[ii] McKittrick writes, “Etymologically, demonic is defined as spirits – most likely the devil, demons, or deities – capable of possessing a human being. It is attributed to the human or the object through which the spirit makes itself known, rather than the demon itself, thus identifying unusual, frenzied, fierce, cruel human behaviors. While demons, devils, and deities, and the behavioral energies they pass on to others, are unquestionably wrapped up in religious hierarchies and the supernatural, the demonic has also been understood in terms that are less ecclesiastical. In mathematics, physics, and computer science, the demonic connotes a working system that cannot have a determined, or knowable, outcome. The demonic, then, is a non-deterministic schema; it is a process that is hinged on uncertainty and non-linearity because the organizing principle cannot predict the future. […] With this in mind, the demonic invites a slightly different conceptual pathway – while retaining its supernatural etymology – and acts to identify a system (social, geographic, technological) that can only unfold and produce an outcome if uncertainty, or (dis)organization, or something supernaturally demonic, is integral to the methodology” (McKittrick, xxiv). Moreover, McKittrick expands upon a concept from Sylvia Wynter, who “underscores the ways in which subaltern lives are not marginal/other to regulatory classificatory systems, but instead integral to them. This cognition, or demonic model, if we return to the nondeterministic schema described above, makes possible a different unfolding” (McKittrick, xxv).

[iii] The protagonist also comments that she has become a “perfect specimen of bare life” (134), bare life a phrase from Giorgio Agamben’s seminal work of political philosophy of the Holocaust, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1995), which argues that the nomos of modernity is the concentration camp and that modern democracies tend to become turn-key dictatorships; all that is required is a declaration of the “state of exception” born of political expediency. Under the state of exception that removes undesirables to concentration camps, those who the dictatorship renders stateless are reduced to “bare life” – a state of extreme violability and social abandonment in the absence of politically conferred human rights.

[iv] For a great book on the stupidity of statecraft that refines and evacuates space of all its life-giving diversity, see Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998) by James C. Scott.

[v] “There would be, he wrote, in that exquisite hand I had never seen personally but could imagine so well in my mind’s eye, no wind turbine; there would be no deer fencing, there would be no planting of trees or management of rushes, no bees, no new builds, no council tax on second homes or short-term lets, no tourist tax, no reintroduction of beavers, no wildcats, no bears, no foxes, no foreigners, only things as they had always been, only Nature and the gaze. O rhododendrons! (They grew in profusion around his house.) O such themes!” (69).

I will. I’ll gather my thoughts but truthfully, although I can’t add the references you did, I feel much the same. My review would be simpler, but not different.

Absolutely incredible! Well worth the effort and time it took to write this outstanding essay. I would like Sarah Bernstein to read it. Wouldn’t you? Outstanding song choices, as usual. You have such a gift, Rebecca!