Madwomen and Witches on The Femicide Continuum: The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox (2006) by Maggie O’Farrell

Spoilers are limited, but I highly recommend reading the book!

They pass by a ruin, bedded into the grass like old teeth. Esme stops to look at it.

‘It’s an old abbey,’ Iris says, poking at a low, crumbling wall with her toe. Then, remembering something she’d read once, she says, ‘The Devil is supposed to have appeared here to a congregation of witches and told them how to cast a spell to drown the King.’

Esme turns to her. ‘Is that so?’

Iris is a little taken aback by her intensity. ‘Well,’ she dissembles, ‘it was what one of them claimed.’

‘But why would she say it if it wasn’t true?’

Iris has to think for a moment, wondering how to put it. ‘I think,’ she begins carefully, ‘that thumbscrews can make you pretty inventive.’

‘Oh,’ Esme says. ‘They were tortured, you mean?’

Iris clears her throat, which makes her cough. Why had she begun this conversation? What had possessed her? ‘I think so, she mumbles, ‘yes.’

Esme walks along beside one of the walls, putting one foot in front of the other in a deliberate, rhythmic fashion, like a marionette. At a cornerstone, she stops. ‘What happened to them?’ she asks.

‘Er…’ Iris looks around wildly for something to distract Esme. ‘I’m not sure.’ She gestures extravagantly out to sea. ‘Look! Boats! Shall we go and see?’

‘Were they put to death?’ Esme persists.

‘I… um… possibly.’ Iris scratches her head. ‘Do you want to go and see the boats? Or an ice-cream. Would you like an ice-cream?’

Esme straightens up, weighing the pebble in her palm. ‘No,’ she says. ‘Were they burnt or strangled? Witches were strangled to death in parts of Scotland, weren’t they? Or buried alive.’

Iris has to resist an urge to cover her face with her hands. Instead she takes Esme by the arm and leads her away from the abbey. ‘Maybe we should head home. What do you think?’

Esme nods. ‘Very well.’

Iris walks carefully, plotting their route back to the car in her head, taking care to avoid any further historical sites.

~ The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, pp.134-136

“Same Old Energy” by Kiki Rockwell

The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox (2006) by Maggie O’Farrell is a propulsive feminist Gothic work of literary fiction (and it’s relatively short!). The story revolves around Esme Lennox and her great-niece, Iris, a young, independent 21st-century working woman with romantic troubles. Iris Lockhart lives in Edinburgh on the top floor of her grandmother’s historic mansion, which she has divided into flats, selling all but the one she occupies. One day Iris learns that she has a great-aunt named Euphemia “Esme” Lennox, who has never been spoken of, having been involuntarily confined to the local lunatic asylum for the last sixty years, and who is being discharged into Iris’s care due to the asylum’s shuttering. Meanwhile, Esme’s sister, Iris’s grandmother, Kathleen “Kitty” Lockhart (née Lennox), lives in a nursing home for the memory impaired, where she slips in and out of lucidity, her mind ravaged by Alzheimer’s disease. I will try to contain the spoilers, especially the big secret that gets unearthed in the novel (it sure does deliver!), but I encourage you to read this quick and beautiful story. I sobbed when the secret was revealed.

As the above passage suggests, The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox explicitly links the psychiatric imprisonment and abuse of women in the late modern period to the femicidal witch-hunts of the early modern period, demonstrating that they exist on a continuum of institutionalized misogyny that steals women’s bodies, breaks their spirits, and wastes their lives. Drawing on feminist studies and mad studies, I read The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox as a powerful indictment of the “shibboleths of progress,” or hollow progress narratives, of Western society that conceal the misogynistic violence that lies at Western modernity’s core – a hidden-in-plain-sight history of sex subjugation both gratuitous and quotidian. In confronting this occluded history, The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox asks the reader to consider what it would look like for Western women to become truly self-determining and sovereign beings, free both in mind and body.

“Us and Pigs” by Sofia Isella

It is also noteworthy that in the above passage, Iris, unsettled, wants to avoid discussing the witch-hunts, while Esme presses the question, letting Iris sit with her discomfort and cognitive dissonance, challenging Iris to confront the state’s historical – and ongoing – wars on women and thereby to achieve new wisdom.

Radical Feminist Analysis of the Early Modern Witch-Hunts.

In Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (2004), feminist-autonomist scholar Silvia Federici analyzes the femicidal witch-hunts that were coeval with the rise of capitalism through a radical feminist-materialist lens, framing them as a pretext for ‘primitive accumulation’ (originary violence and theft that become foundational to the new political economy) that expropriated women’s bodies and labor, both productive and reproductive, stripped them of the economic and political rights that they enjoyed in the medieval period (surprisingly!), and transformed them into docile and subservient objects of male exploitation. She writes that, in the early modern period, “new laws and new forms of torture were introduced to control women’s behavior in and out of the home”; these “expressed a precise political project aiming to strip them of any autonomy and social power” (Federici, 101).[i] When the campaign of violence ended, “women themselves became the commons” (Federici, 97).

“Labour” by Paris Paloma

The witch, Federici explains, is “the embodiment of a world of female subjects that capitalism had to destroy: the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, the obeha woman who poisoned the master’s food and inspired the slaves to revolt” (Federici, 11). The witch represents the unruly, dissident woman who exerts her free will and agency. The witch also represents women’s traditional systems of wisdom and knowledge that had to be destroyed for the new capitalist order to emerge victorious, from the healing arts to subsistence agriculture to collective resistance: “Though the witch-hunt targeted a broad variety of female practices, it was above all in this capacity – as sorcerers, healers, performers of incantations and divinations – that women were persecuted. For their claim to magical power undermined the power of the authorities and the state, giving confidence to the poor in their ability to manipulate the natural and social environment and possibly subvert the constituted order” (Federici, 174).[ii]

Only a regime of widespread political terror could strip women of their bodily autonomy, free spirits, willful minds, ancient systems of knowledge, and social freedom. Once this was achieved, the female archetype underwent a transformation: “While at the time of the witch-hunt women had been portrayed as savage beings, mentally weak, unsatiably lusty, rebellious, insubordinate, incapable of self-control, by the 18th century” a new, purified image of femininity had taken over, which depicted them as “passive, asexual beings, more obedient, more moral than men, capable of exercising a positive moral influence on them” (Federici, 103). Federici concludes, “The witch-hunt […] was a war against women; it was a concerted attempt to degrade them, demonize them, and destroy their social power. At the same time, it was in the torture chambers and on the stakes on which the witches perished that the bourgeois ideals of womanhood and domesticity were forged” (186).

Esme Lennox and the Witch-Hunts.

Esme represents the figure of the witch; the willful, disobedient woman, she refuses to submit to her gender prison. As a teenager, she wants to continue her schooling. A daydreamer, she enjoys an active imagination, one she wants to feed through continual reading (girl, I relate). To the horror of her parents, she aims to work and never to marry. On a whim, she decides that she’ll travel the world. A free spirit, she simply can’t sit still, and she doesn’t think to stifle her natural, budding sexuality. For all this, she must be punished – “strapped to a chair” during lunch (6), chastened, humiliated, and finally, imprisoned and violently controlled through electroshock therapy, medical sedation, and solitary confinement. The aim of psychiatry is to mutilate an intelligent, strong-willed woman with a symphonic, rich inner life and replace her with an outwardly docile, mentally evacuated, infantilized, broken shell of a woman.

Mad Studies.

‘Don’t leave me here!’ she cries out. ‘Please! Please don’t. I’ll be good, I promise’ ~ The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, p. 176

Mad studies is a critical framework grounded in radical humanism and compassion that analyzes methods of psychiatric treatment, evaluating whether they have served to heal or harm people with psychiatric diagnoses. This critique emerges from the lived experience of psychiatric abuse survivors and conscientious whistleblower-practitioners and has crucially intervened in the prevailing psychiatric status quo.[iii]

Mad studies argues that mainstream psychiatry has served as a tool of violent social control to discipline, punish, and imprison subversives who challenge hegemony’s systems of oppression and social policing. While deviant women, queer people, and people of color have been the primary targets of the psychiatric regime, straight white men, also subject to the gender code’s strict behavioral prescriptions, have fallen prey to psychiatry’s clutches. Psychiatric labels such as hysteria, which figures women’s minds as prone to madness due to unstable wombs; drapetomania, created to pathologize Black enslaved persons for desiring to escape to freedom; and naming homosexuality and gender deviance as psychiatric disorders in the DSM all attest to psychiatry’s punishment of rebellion and difference. Significantly, the early psychiatric establishment conjured psychological distress, labelled “madness,” as demonic possession, just as Church and state officials conceived of “witches” as enslaved to Satan.

Much has been written on psychiatry as a means of brutal retribution against social dissidents.[iv] Psychiatric methods such as imprisonment in mental facilities, psychosurgeries such as lobotomy, questionable treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy, and psychotropic drugs that stupefy and cause harmful side effects (tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, psychosis) all testify to the abuses that have been justified under the guise of psychiatric care. Numerous exposés have aired psychiatry’s dirty secrets.[v]

I came to mad studies as a community organizer who witnessed psychiatry’s ongoing abuses firsthand, having worked in Chicago, where a preponderance of low-income people with psychiatric diagnoses were being warehoused, overdrugged, and economically exploited.[vi] Conscientious practitioners and psychiatric abuse survivors introduced me to the work of Robert Whitaker and to Judi Chamberlin, particularly On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System (1978) and her article “Confessions of a Noncompliant Patient” (1998). In “Confessions,” Chamberlin writes,

One of the reasons I believe I was able to escape the role of chronic patient that had been predicted for me was that I was able to leave the surveillance and control of the mental health system when I left the state hospital. Today, this is called ‘falling through the cracks.’ Although I agree that it is important to help people avoid hunger and homelessness, such help must not come at too high a price.

Help that comes with unwanted strings – ‘We’ll give you housing if you take medication,’ ‘We’ll sign your SSI papers if you go to the day program’ – is help that is paid for in imprisoned spirits and stifled dreams. We should not be surprised that some people will not sell their souls so cheaply.

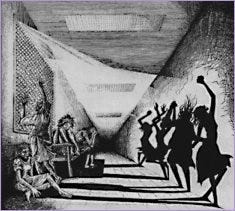

Let us celebrate the spirit of non-compliance that is the self struggling to survive. Let us celebrate the unbowed head, the heart that still dreams, the voice that refuses to be silent. I wish I could show you the picture that hangs on my office wall that inspires me every day, a drawing by Tanya Temkin, a wonderful artist and psychiatric survivor activist. In a gloomy and barred room, a group of women sit slumped in defeat, dressed in rags, while on the opposite wall their shadows, upright, with raised arms and wild hair and clenched fists, dance the triumphant dance of the spirit that will not die (Chamberlin, 1998).

Chamberlin escaped the system in time to resume her life, so that it wouldn’t be irrevocably stolen from her. Many women weren’t so lucky and languished in their psychiatric prisons. Esme represents the woman who got out at the proverbial eleventh hour, but the horrors she endured are unimaginable. Unbidden, dark memories surface: “the convulsions, the thrashing body, the lolling tongue, and then the awful stillness” (123-124). In a wave of lucidity that ends as abruptly as it begins, Esme’s sister Kitty recalls,

And they took me down to this terrible place like a dungeon and instructed me to peep through this small hole in a door with iron locks. And in this camera obscura I saw a creature. A being. All wrapped up like a mummy but with a face that was bare and split and bleeding. It was creeping, creeping, its shoulder pressed into the softened wall, mumbling to itself. And I said, no, that’s not her, and they said, yes, it is. I looked again and I saw that perhaps it was and I— (225).

The story has many more Gothic elements – a decrepit asylum of hidden horror chambers with a sinister architectural aesthetic; an old house that is haunted for Esme; Esme’s mind, which serves as both refuge and prison; and Kitty, the sister, the symbol of the self-interested woman who collaborates with the malevolent forces of hegemony and cannot see that by poisoning the wells of other women, she sickens herself in the process and causes her own suffering.

In full feminist Gothic splendor, this story requires revenge fantasy fulfillment.

“Burn Your Village” by Kiki Rockwell

Amazingly, though not surprisingly, there are musical playlists curated for witchcore vibes. What a time to be alive.

My hope for Iris at the end of the text is that she finds ways to become deliberately self-determining and self-possessed — of her mind, her body, her sexuality, her work, her loves, her experiences, and her passions. I hope that she can reclaim the legacy of the witch and defiantly say I am the granddaughter of the witches you could not burn.

Post-Script.

“Maimonides Dream Laboratory” by Paula Pryce

I couldn’t really find any suitable feminist anti-psychiatry songs (please link if you have ideas), but my mind kept going back to this one, written by a psychiatric survivor who used to be a friend. Though it hints at psychiatric abuse, the content of the song is about the Maimonides Dream Laboratory experiment, and I like this blurring that troubles the distinction between the mad and the visionary. Esme has a similar thought about sedation, perhaps here figured as a mystical experience that an altered state brings, much like the vision-quest: “There is a moment, under sedation, before full unconsciousness swallows you, when your real surroundings leave an impression on that floating, imagistic delirium that holds you under. For a short period you inhabit two worlds, float between them. Esme wonders for a moment if the doctors know this” (221-222).

For haunted house and nostalgia vibes, I’m also thinking about this one.

“Entropy Hall” by Paula Pryce

In Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado sets two poetic epigraphs, and one reads, My body is a haunted house that I am lost in.

For a film depiction of 19th-century psychiatric abuse, I highly recommend The Mad Women’s Ball. I found the book unremarkable, but the film was incredibly powerful and moving.

[i] Through various “strategies and violence,” “male-centered systems of exploitation have attempted to discipline and appropriate the female body” (Federici, 15); “women’s bodies have been the main targets, the privileged sites, for the deployment of power-techniques and power-relations” (Federici, 15).

[ii] Federici declares, “For the witch-hunt destroyed a whole world of female practices, collective relations, and systems of knowledge that had been the foundation of women’s power in pre-capitalist Europe, and the condition for their resistance in the struggle against feudalism” (Federici, 103).

[iii] As Robert Whitaker explains in Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America (2010), a human rights-based critique emerged in the mid-20th century that “questioned the ‘medical model’ of mental disorders and suggested that madness could be a ‘sane’ reaction to an oppressive society. Mental hospitals might better be described as facilities for social control, rather than for healing, a viewpoint crystallized and popularized in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (Whitaker, 264).

[iv] For example, see “Declared Insane for Speaking Up: The Dark American History of Silencing Women Through Psychiatry” by Kate Moore. In the late 1960s, Black Americans protesting their internal colony status in urban wastelands through unrest were labeled criminally insane; while Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called the urban riot “the language of the unheard” and dispossessed, psychiatric professionals labeled its perpetrators schizophrenic (see The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease by Jonathan Metzl). In the 1970s, conscientious practitioner Dr. Peter Breggin waged a campaign to stop the State of Mississippi from lobotomizing Black children in its care.

[v] One example is “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors” by Joseph Shapiro.

[vi] Warehoused: in institutions called IMDs (Institutes of Mental Diseases); overdrugged: by rapacious psychiatrists in collaboration with predatory pharmaceutical companies, and economically exploited: in Medicare fraud schemes.

Rebecca Gordon Exquisite music selections, as always. We have many women in San Marcos…herbalists, doulas, tarot readers, who subscribe to Wiccan beliefs.

Wiccans differ from more mainstream religions in several ways, including:

Lack of formal structure: Wicca doesn't have a formal institutional structure like a church.

Emphasis on ritual and experience: Wiccans place more emphasis on ritual and direct spiritual experience than belief.

Ethical code: Wiccans have an overriding rule, "Harm none and do as you will".

The use of psychiatry can be helpful I think in certain scenarios but so harmful in others as you pointed out. It takes power and free will away, mostly of course in this book, which I am intrigued to read, from women. Not in the case of women I know, witches or not, who know their strength and power and exercise it through kindness and caring for others, which might be the case of the characters in this novel. Masterful writing as always, Rebecca!